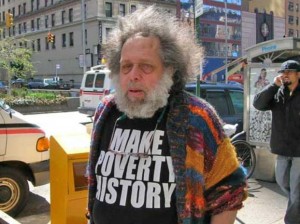

Marshall Berman was a man who was, in every way, hard to miss. At first glance, his unruly mane, fantastic t-shirts, and kaleidoscopic sweaters, made it immediately apparent that he was an intellectual who trafficked well outside the norms of academia. His work took us on a ride as wild as his aesthetic. Traversing disciplinary and cultural boundaries, he artfully captured and beautifully rendered the dynamism of modernity. In crossing these boundaries, he helped us overcome our own, and allowed us to see our world, one another, and ourselves through new, awestruck eyes, if only for a moment. Like the world he sought to disclose, his work was transformative, leading many to experiences of personal revelation. In a world that so often compels us to be narrow, Marshall showed us the possibilities revealed by radical openness.

He offers one description of this openness in his most-loved book, All That is Solid Melts into Air. Therein he explained that to be modern is “to experience personal and social life as a maelstrom, to find one’s world and oneself in perpetual disintegration and renewal, trouble and anguish, ambiguity and contradiction…” In this, we have little choice; the condition of our experience is modern, and as such so are we. How we relate to our condition, however, is what separates the modernist from the malcontent. He continued, “To be a modernist is to make oneself somehow at home in the maelstrom, to make its rhythms one’s own, to move within its currents in search of the forms of reality, of beauty, of freedom, of justice, that its fervid and perilous flow allows.” It would be difficult to find a more fitting epitaph for Marshall, who was more at home in this world than any other I’ve met. His love for, appreciation of, and delight in the harnessed creativity of our species was so great and so unwavering, that it could at times be hard to understand. How could a man so acutely aware and intimately affected by the cruelty of modernity remain so open to it? I think that for Marshall, finding and fighting for beauty, freedom, and justice required an unwavering faith that they could be found. I think it was this faith that allowed him to look for, and find it, in the darkest of places.

His life and work offer endless examples of the beautiful things that come from the dark, but one that has particularly struck with me is a scene from Ric Burns’ iconic New York documentary. Like many others, I’ve found myself returning to Marshall’s work in the few weeks since his passing, and there’s comfort in seeing and hearing him talk about himself and our city. The image that persists in my memory, however, isn’t one of him onscreen, but one that he paints of himself as a child. Standing on the Grand Concourse overlooking the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, he describes an engineering feat that “was quite beautiful and sublime”, but one that arose from the demolition of his own neighborhood at the hands of “that bastard,” Robert Moses. He depicts himself on a precipice, surveying his environment being shaped and re-shaped by the twin forces of creation and destruction, and the urgent, paradoxical feelings of agony and ecstasy these forces evinced in him. In classic Marshall Berman style, he captures with a handful of casual sentences, the essence of the modern experience—an experience as terrifying as it is exhilarating, and one that constantly threatens to overtake those who are not open to it.

These examples highlight the kernel of Marshall’s thought that has had the most transformative effect of my own. Namely, that in order to find meaning in the modern world, we must believe that it can be found, and be open to finding it. Otherwise, we risk falling into the trap of nihilism and pessimism that have become all too prevalent. There’s a way of seeing the world, he once said to me, that “reduces everything to shit,” and that wasn’t the world he wanted to live in. But more to the dialectical point, it wasn’t the world he lived in. This has been an important lesson for me. And though I suspect I’ll always be more inclined to levy criticism than Marshall was, I have him to thank for helping me find a more sensitive, strong, creative voice.

All of this is to say, Marshall Berman made an impact that was hard to miss, which is precisely what makes missing him so hard.

[published in the October 2013 issue of the Advocate]